After Years Lost, Identity Reclaimed

Detective Work Leads Smithsonian Team to Give Unearthed Body a Name

By Michael E. Ruane

Washington Post Staff Writer

Thursday, September 20, 2007; B01

He was a sickly orphan who had died of pneumonia as a teenager and then

was left behind when the cemetery where he was buried in Northwest

Washington moved a decade after his death.

He lay lost and forgotten beneath the sprawl of the city, while six

generations and 155 years passed by.

And when his body was accidentally unearthed by a construction crew in

2005 -- still clad in his fine white burial suit and encased in an iron coffin --

researchers at the Smithsonian Institution vowed to find out who he was.

Now they say they have.

This week, after a two-year project that unfolded like a detective story,

experts at the National Museum of Natural History said that the mysterious

boy in the iron coffin has been identified: He was William T. White, about 15,

from Accomack County on Virginia's Eastern Shore.

He had been buried in a cemetery that probably belonged to Columbian

College, the precursor to George Washington University, in what is now

Columbia Heights, and had been a student at the college preparatory school

when he died Jan. 24, 1852.

Smithsonian anthropologist Douglas W. Owsley said yesterday that the boy

was just over five feet tall and probably had been an unhealthy youth,

because of a hole that was discovered between two chambers in his heart.

The identification was made after museum researchers, led by Deborah

Hull-Walski and Randal Scott, figured out that the youth might be White,

constructed a 788-person family tree -- a diagram that stretched the length of a wall -- and tracked down a descendant in

Lancaster, Pa.

The descendant, Linda Dwyer, 64, a night clerk in a convenience store, agreed to provide a sample of her DNA, obtained via a

mouth swab, and when that was compared with DNA taken from the boy's left shinbone, it matched.

She said elated Smithsonian researchers called her with the news, saying: " 'It's you! It's you!' "

"I think it's awesome," Dwyer said yesterday, adding that she believes she is White's great-great-great-grandniece. "The whole

technology of finding me and putting it all together. . . . It's so cool."

The museum also had computerized facial reconstructions done by experts from the National Center for Missing & Exploited

Children in Alexandria. The images depict a pleasant-looking youth about the age of a high school freshman, who a century

and a half after his death again has a name.

"It's more than a name," Hull-Walski said. "It's his whole story. It's his family's story. It's who he was, what he did. . . . It's

everything."

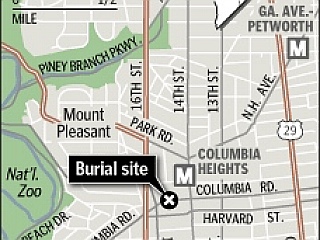

The saga began April 1, 2005, when construction workers digging beneath a gas line outside an 80-year-old apartment

building at 1465 Columbia Rd. NW stumbled on the elegant coffin.

The workers locked it in an empty building, where, on April 4, vandals broke in and smashed the coffin's oval glass faceplate

and metal cover.

But the Fisk and Raymond "metallic burial case" was a big clue. Such coffins were expensive, often reserved for the well-to-do,

and were popular between 1850 and 1860, Hull-Walski and Scott said in an interview Tuesday at the Smithsonian's Museum

Support Center in Suitland. The cases also were airtight.

The museum, which Owsley said investigated the case as a public service and research opportunity, took custody of the coffin

after the vandalism, and in August 2005, he and a team of pathologists unbolted the lid and examined the body and the

clothing.

The boy was extremely well preserved and clad in white cotton clothing that included a pleated shirt and vest with cloth-

covered buttons, flared trousers, darned socks and ankle-length underdrawers.

An autopsy indicated that the boy probably died of lobar pneumonia, and the clothing style hinted that he had probably died in

the 1850s.

But why was he buried in the now-residential neighborhood of Columbia Heights?

The investigation revealed that Columbian College had once been there, and a page from a 1970 history of George

Washington University stated that the old college had a cemetery. Further research showed that the original cemetery was

moved in 1866 from the periphery of the college grounds to the main campus. And it was during this move that the iron coffin

was probably left behind.

This might have been because the tombstone was absent or had been misplaced during the Civil War, when the college was

the site of two sprawling military hospitals, the researchers said.

The team then began poring over lists of obituaries from the 1850s compiled from local newspapers and quickly hit what

looked like pay dirt.

The May 27, 1852, edition of Washington's Daily National Intelligencer carried an obituary for Lemuel P. Bacon, 12, the son of

Columbian's president, Joel Bacon.

It seemed perfect.

The museum had the samples of the coffin boy's mitochondrial DNA, which Smithsonian experts said can be traced and

matched via female descendants over many generations. Hull-Walski and Scott developed a Bacon family tree and located a

descendant in Texas. But when the descendant's DNA was compared with the boy's, it did not match.

Neither researcher was surprised. It was too easy.

Another apparent breakthrough followed. The Jan. 28, 1852, edition of the Intelligencer carried a brief obituary for a William

Taylor White, of Accomack, who had died "at college hill" four days earlier.

The researchers obtained a digest of old wills for Accomack County and found one in which a guardian had left White money

for his education. This time, Scott said, "we really felt like we had the right person."

The same digest contained the will of a Levin White, who had a son named William T., and who the researchers figured must

have been the boy's late father. "It matched up beautifully," Scott said. But when a descendant of Levin White was located in

Baltimore, to the experts' surprise, her DNA did not match. "That was devastating," Scott said.

But they had one more prime candidate. The team had also found an obituary for a William Henry White, who had died Sept.

29, 1852, at the age of 14. There was no connection to the college, but the boy's father, Mathias, had been a Pennsylvania

Avenue undertaker who used Fisk and Raymond coffins.

Again a descendant was traced, this time to suburban Maryland. But again the DNA did not match.

It was now summer 2006, and the team had been working on the case for a year. The boy's body was being preserved at the

museum, where it remained yesterday, awaiting final disposition, encased in a white body bag inside a metal cooler. But the

researchers appeared no closer to knowing his name.

"What do we do now?" Hull-Walski said they thought.

Yet they remained determined.

"He'd been left behind that initial time," Scott said. "It wasn't going to happen again."

Hull-Walski said: "We wanted to know who he was. We just wanted to give him a name."

In the spring, she found a crucial clue. Searching through a computer database of the Washington Intelligencer, she stumbled

on another notice of the death of William T. White. But it wasn't an obituary.

It was a heartfelt "resolution" drawn up by his college friends, expressing their anguish at the loss of one who "was bound to us

by the tenderest ties of friendship." Somehow it had not turned up in prior research, but it reinforced to Hull-Walski that,

despite the DNA, William T. White had to be the coffin boy. She showed the notice to Scott. "It's him," she told her colleague.

But where had they gone wrong?

"So we started again," Hull-Walski said. She appealed to colleagues on the Eastern Shore, where White was born, explaining

the problem and asking for help.

She soon got it. A local genealogist called her with the news that the Levin White she thought was William's father, and whose

family tree she had traced, was from a different White clan.

There was the research mistake, Hull-Walski realized, and that's why the DNA didn't match. "It was a relief," she said.

Yet it still didn't tell her who the boy's father was. Without that knowledge, no descendants could be traced, and no modern

DNA could be checked.

Then more help came. Two acquaintances visiting an Accomack records office found an 1850 court document that referred to

White's status as an orphan -- and listed the name of his deceased father, William A. White.

"Bingo," Hull-Walski said.

The team quickly traced the family and located Dwyer in Lancaster. Hull-Walski and a colleague went to visit Dwyer Aug. 1,

and took the DNA swab in a quiet corner of a Denny's restaurant.

The comparison, performed for free by Mitotyping Technologies, of State College, Pa., came through a week or so later.

The DNA matched. And the orphaned youngster from a bygone time finally had his identity back.

"You just kind of tear up," Hull-Walski said. "It just felt so good. It felt so doggone good."

© 2007 The Washington Post Company

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/09/19/AR2007091902409_pf.html